Ireland’s Past – a Prelude to Disaster

To fully understand The Great Hunger, its impact on the Irish people, and the resulting diaspora of the Irish nation, it is essential to examine both the history of Ireland and events leading up to the catastrophe. The twelfth century marked the beginning of eight hundred years of English rule and Irish resistance. Throughout the centuries, English laws were enacted to strip the Irish not only of their land, but also of their unique cultural heritage, their customs, language, laws,and religion. These unjust laws punished the Irish simply for being who they were.

To fully understand The Great Hunger, its impact on the Irish people, and the resulting diaspora of the Irish nation, it is essential to examine both the history of Ireland and events leading up to the catastrophe. The twelfth century marked the beginning of eight hundred years of English rule and Irish resistance. Throughout the centuries, English laws were enacted to strip the Irish not only of their land, but also of their unique cultural heritage, their customs, language, laws,and religion. These unjust laws punished the Irish simply for being who they were.

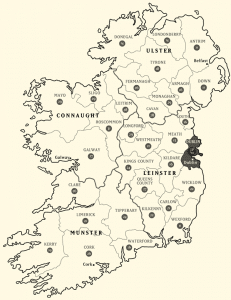

The mid-sixteenth and seventeenth centuries saw the greatest confiscation of the most fertile Irish land located in the eastern part of the country. By 1691, approximately eighty percent of the land had been taken, forcing many Irish people to flee westward. The results of these forced displacements were evident in the 1841 census, which indicated that the greatest population density was now found in western Ireland, a region where, unfortunately, the poorest farmland was located.

This brutal confiscation of land was followed by more than a century of “Penal Laws.” These policies, designed to virtually enslave the Gaelic majority by allowing foreign landowners to possess large tracts of land, reduced Irish land holdings, thereby eliminating any real participation of the Irish people in the governing of their own country. To vote, one had to own property. The land was usually owned as large estates by absentee English landlords who subdivided it into smaller parcels and then rented it at predatory rates to their Irish tenants, ironically, often to the very same tenants whose families had once owned the land.

The impoverished Irish farmers warded off eviction by paying the high rents with the crops that they grew. However, to sustain their families, tenants needed to find an additional crop to grow for their own food; a crop that would prosper in even the poorest soil. With its ability to produce a strong yield, its high caloric content, and its rich supply of vitamin C, potassium and carbohydrates, the potato became the perfect solution for staving off their hunger. Because virtually no alternative food was available, the potato became the staple of the Irish diet. Thus the stage was set for a catastrophe when this source was lost. Go Back…